Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know, or can you guess, the language?

I spent last week in Donegal in the northwest of Ireland learning some more Irish, and learning about the area where I was, Glencolmcille (Gleann Cholm Cille in Irish). I had a great time, met some interesting people, and saw some beautiful places.

The course I did this time is called Language and Landscape: The Heritage of Gleann Cholm Cille / Teanga agus Timpeallacht: Oidhreacht Ghleann Cholm Cille. It involves Irish language classes in the mornings, and walks, talks, trips and other activities in afternoons and evenings. It’s run by Oideas Gael, an Irish language and culture centre in the southwest of Donegal which is celebrating its 40th year this year. I’ve been there for 16 of those years: every year from 2005 to 2019, and in 2024.

In previous years I’ve done courses there in Irish language, harp and bodhrán playing, and Irish sean-nós singing. I always enjoy my time there, which is why I keep going back. Most of the people there were from Ireland, and there were also people from the USA, UK, France, Canada, Portugal, Austria and Russia.

So, as well as practising my Irish, I got to speak other languages like French, German and Japanese. In class our teacher also taught as a few interesting words in Ulster Scots.

These include:

Gomeral is a diminutive of Middle English gōme (man, warrior, husband, male servant), from Old English guma (male, hero), from Proto-Germanic *gumô (man, person), from Proto-Indo-European *ǵʰmṓ (man, person) [source].

Clart comes from Middle English *clart, from biclarten (to cover or smear with dirt) [source].

I’m not sure where the other words come from.

One thing we did in class was to come up with some new proverbs in Irish. Incidentally, the Irish word for proverb is seanfhocal, which literally means “old word”. So here are a few new old words:

I’m off to Ireland tomorrow for a week of learning Irish and learning about the landscape of Glencolumcile (Gleann Cholm Cille) in Donegal. I’ve been there many times before – every year from 2005 to 2019, but this is the first since then. I’ll probably see quite a few people I know, and meet some new ones as well, and I’m looking forward to it.

I rarely get to speak much Irish in Bangor. There are a few Irish speakers here, and we conversations in Irish occasionally. Apart from that, I sometimes listen to Irish songs and Irish language radio, and have been brushing up my Irish on Duolingo recently.

While I’m there, I probably won’t have a lot of time to work on Omniglot. Normal service will resume after I get back.

Greetings fellow Earthlings and anyone else who might be reading this. Did you know that this word originally meant farmer?

These days in Science Fiction, an Earthling is “an inhabitant of Earth, as opposed to one of another planet; specifically, a sentient member of any species native to Earth.”

In the 17th century is referred to “A person who is materialistic or worldly; a worldling.” and in the 16th century, it referred to “An inhabitant of Earth, as opposed to one of heaven.” [source]

Going back further, it meant one who tills the earth, a farmer, a husbandman or a ploughman. It comes from Middle English erthling (farmer, ploughman), from Old English ierþling, eorþling (farmer, husbandman, ploughman), from eorþe (ground, dirt, planet Earth), from PIE *h₁er- (earth) [source]

Other interesting words suffixed with -ling include:

There’s also underling (a subordinate or person of lesser rank or authority), and it’s rare antonym overling (a superior, ruler, master) [source]

You can see more of these on: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/-ling#English

Foods, and the words that describe them, can travel around the world. For example, tea comes from China, and so do words for tea in many languages. Similarly, avocado, chocolate, tamale, tomato come from Mexico (both the words and the foods).

Those words came to Europe from other continents, and I recently discovered some words that travelled from Europe, or Western Asia, to many other parts of the world.

It started with the Proto-Indo-European word *médʰu (honey, mead), which spread throughout Europe and Asia, and possibly as far as China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam [source].

Descendants of *médʰu include:

The Irish name Méabh (Maeve) also comes from the same roots, via Middle Irish medb (intoxicating) [source]. For more details of related words in Celtic languages, see this Celtiadur post: Honey Wine

It also reached China, where it became mīt (honey) in Tocharian B, and was possibly borrowed into Old Chinese as *mit (honey), which became 蜜 (mì – honey) in Mandarin, 蜜 (mat6 [mɐt˨] – bee, honeybee) in Cantonese, 蜜 (mitsu – honey, nectar, moasses, syrup) in Japanese, 밀 (mil – beeswax) in Korean, and mật (honey, molasses) and mứt (jam) in Vietnamese [source].

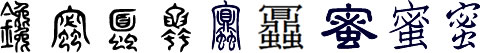

Evolution of the Chinese character for honey (蜜)

See also: https://hanziyuan.net/#蜜

Someone who is supercilious is arrogantly superior, haughty or shows contemptuous indifference.

Supercilious comes from the Latin superciliōsus (haughty, supercilious) from supercilium (eyebrow, will, pride, haughtiness, arrogance, sterness, superciliousness) from super- (above, over) and cilium ( eyelid), from Proto-Italic *keljom, from PIE *ḱel-yo-m, from *ḱel- (to cover) [source].

Equivalents of supercilious in other languages include:

The word cilium also exists in English, and means:

Related words in other languages include: cil (eyelash), and sourcil (eyebrow) in French, ceja (eyebrow, rim, edge) in Spanish, and ciglio (eyelash, eyebrow, border, edge, side) in Italian [source].

Other (eye)brow-related words include:

Highbrow first appeared in print in 1875, and originally referred to the ‘science’ of phrenology, which suggested that a person of intelligence and sophistication would possess a higher brow-line than someone of lesser intelligence and sophistication [source]. Lowbrow was also conntected to phrenology and first appeared in about 1902 [source]. Middlebrow first appeared in Punch magazine in 1925 and is based highbrow and lowbrow [source].

If something is completely devoid of cultural or educational value, it could be said to be no-brow / nobrow, a word popularized by John Seabrook in his book Nobrow: the culture of marketing, the marketing of culture (2000) [source].

Incidentally, raising or furrowing your eyebrows is used to show you are asking a question in British Sign Language (BSL). Do other sign languages do this?

Do you know of any other interesting brow-related expressions?