Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language?

What links the word tarragon to words like dragon and drake?

Tarragon is a perennial herb of the wormwood species Artemisia dracunculus native to Europe and Asia. It’s also known as estragon, dragon’s wort or silky wormwood. Other names are available.

The word tarragon comes from Middle French targon (tarragon), from Medieval Latin tragonia (tarragon), from Arabic طَرْخُون (ṭarḵūn – tarragon), from Ancient Greek δρακόντιον (drakóntion – dragonwort, Dracunculus vulgaris), from δράκων (drákōn – dragon, serpent) [source].

The word dragon comes ultimately from the same Ancient Greek roots, via Middle English dragoun (dragon, drake, wyrm), Old French dragon (dragon), and Latin dracō/dracōnem (dragon) [source].

The word drake (a mayfly used as fishing bait, dragon [poetic], fiery meteor), also comes from the same Ancient Greek roots, via Middle English drake (dragon, Satan), Old English draca (dragon, sea monster, huge serpent), Proto-West-Germanic *drakō (dragon), and Latin dracō (dragon) [source].

Incidentally, the word drake, as in a male duck, comes from Middle English drake (male duck, drake), from Old English *draca, an abbreviated form of *andraca (male duck, drake, lit. “duck-king”), from Proto-West Germanic *anadrekō (duck leader), from *anad (duck) and *rekō (king, ruler, leader) [source].

Yesterday I finished reading Tim Brookes’ new book, Writing Beyond Writing – Lessons from Endangered Alphabets, which I found very interesting and would throughly recommend to anybody who is interesting in writing systems and language.

One of the questions asked in the book is ‘What is writing?’

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, writing is

‘letters or characters that serve as visible signs of ideas, words, or symbols’.

According to the The Free Dictionary, writing is:

‘a group of letters or symbols written or marked on a surface as a means of communicating ideas by making each symbol stand for an idea, concept, or thing, by using each symbol to represent a set of sounds grouped into syllables (syllabic writing), or by regarding each symbol as corresponding roughly or exactly to each of the sounds in the language (alphabetic writing).’

Other definitions are available.

Writing systems are generally thought to be ways to represent the sounds and words of language in various ways. However, there are forms of graphic communication that don’t represent sounds or words, but rather ideas, emotions, music, mathematics, time, etc.

In his book, Tim Brookes suggests that these graphical forms could be thought of as forms of writing, and that letters and other symbols from writing systems can be used in decorative, ritualistic and other ways where representing a particular sound or word is not their main purpose.

For example, there is a collection of symbols known as Adinkra which originated with the Gyaman people of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, and which were originally printed onto clothes worn by royalty at important ceremonies. They now appear on clothes, furniture, sculptures and in various other places, and are used as logos.

Each symbol may have a variety of meanings. Here are some examples:

Source: Adinkra Symbols & Meanings

See also: https://www.adinkraalphabet.com/adinkra-symbols/

An alphabet based on these symbols, called Adinkra, was recently created by Charles M. Korankye.

See also: https://www.adinkraalphabet.com/

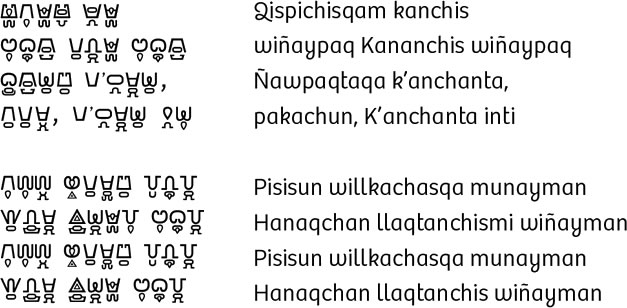

One writing system mentioned in the book is the Silabario Amazónico, which was created in 2016 by Juan Casco, a graphic designer, typographer and visual artist from Ecuador. It is based on graphic symbols used in South America and can be used to write indigenous Amazonian and Andean languages, such as Kichwa, Waorani, and Aymara.

It looks like this:

Source: https://www.behance.net/gallery/79435301/Silabario-Amazonico

I’ve put together a page about it on Omniglot, and have contacted Juan Casco to check if he’s okay with me doing so. It’s not public yet, but you can see it at: https://www.omniglot.com/conscripts/silam.htm.

By the way, Tim Brookes’ Endangered Alphabets Project was inspired by Omniglot. See also the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets.

Do you like to snudge?

To snudge is an old word that means to lie snug or quiet, to save in a miserly manner, or to hoard, and a snudge is a miser or sneaking fellow.

You might also snudge along, which means to walk looking down, with an abstracted appearance. Many people do this while staring at their phones. Or on a cold day, you might snudge over the fire, that is, keep close to the fire.

Snudge is related to snug, which apparently means tight or handsome in some English dialects, and possibly comes from Old Norse snoggr (short-haired), from Proto-Germanic *snawwuz (short, quick, fast).

Related words in other languages include snöggur (short, swift, fast) in Icelandic, snög (neat) in Danish, and snygg (handsome, good-looking, proper, nice) in Swedish.

Snug originally meant compact or trim (of a ship), and especially protected from the weather. Later it came to mean in a state of ease or comfort, then to fit closely, as in snug as a bug in a rug or as in snug as a bee in a box. It also means warm and comfortable, cosy, safisfactory, and can be a small, comfortable back room in a pub (in the UK).

Then there’s snuggle, which means an affectionate hug, or the final remnant left in a liquor bottle, and as a verb, it means to lie close to another person or thing, hugging or being cozy/cosy, or to move or arrange oneself in a comfortable and cosy position.

Instead of snuggling, you might prefer snerdling, croozling, snoodling, snuzzling or even neezling, which all mean more or less the same thing – being cozy and snug.

Do you know any other interesting words for snudging or snuggling?

How about versions of the phrase as in snug as a bug in a rug in other languages?

In Scottish Gaelic there’s cho seasgair ri luchag ann an cruach (“as snug as a mouse in a haystack”), and cho blàth ‘s cofhurtail ri ugh ann an tòn na circe (“as warm and comfortable as an egg in the backside of a hen”),

Sources:

https://www.scotsman.com/news/opinion/columnists/scots-has-more-than-400-words-for-snow-and-we-may-need-them-if-snowmageddon-descends-susie-dent-3959696

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/snudge#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/snug#English

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=snug

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/snuggle#English

https://westcountryvoices.co.uk/weird-and-wonderful-words-week-3/

If you are lost, you might say in French “j’ai perdu le nord”. It means literally that you have lost the north, and can also be translated as to lose one’s way or one’s bearings, to become dazed and confused, or to lose one’s marbles, to lose one’s head or to lose contact.

Alternatively you could say “je suis à l’ouest” (“I am in the west”), which means to be spaced out, to not be with it, or to lose one’s bearings.

Other words for confused in French include confus, perplexe and désorienté.

Confus (confused, confusing, ashamed, embarrassed), comes from Latin cōnfusus (mixed, united, confounded, confused), from cōnfundō ( to pour together, mix), from con- (with, together) and fundō (to pour, shed).

English words from the same roots include confound, confuse, diffuse, found, fuse and profound.

Perplexe (puzzled, perplexed, confused) comes from Latin perplexus (entangled, involved, intricate, confused), from plectō (I weave, I twist), from Proto-Indo-European *pleḱ- (to fold, weave). The English word perplexed comes from the same roots, via Old French.

Désorienté (disorientated, bewildered, confused) comes from désorienter (to disorientate, confuse), from dés- (dis-/de-) and orienter (to orientate, set to north, guide), from Old French oriant (Orient, the East), from Latin oriens/orentem (rising, appearing, originating, daybreak, dawn, sunrise, east), from orior (I rise, get up, appear, originate), from PIE *h₃er- (to stir, rise, move).

The English words disorentated and orientated come from the same roots, as do such words as orient, origin, random and run.

So when you’re disorientated, you’re not sure where the east is. These days maps are generally orientated towards the north, or in other words, north is at the top. However, in Medieval times, maps made by European cartographers were orientated towards the orient or east in the direction of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Other orientations were and are available.

Why is north usually up on maps? The Map Men explain in this video:

Do you have any other interesting ways to say you’re lost or confused?

Here’s a song called “Ai-je perdu le nord ?” (Have I lost the north?) by Clio, a French singer:

Sources:

https://dictionary.reverso.net/english-french/confused

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/confus#French

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/perplexe#French

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/désorienté

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Category:English_terms_derived_from_the_Proto-Indo-European_root_*h₃er-

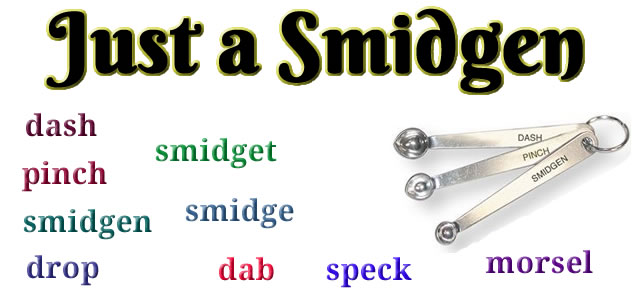

How much is a smidgen? How about a tad, dash, drop or pinch?

These are all terms that refer to small amounts of things. You might see them in a recipe, or use them to refer to other small quantities or amounts. You can even get measuring spoons for some of them.

Apparently a tad is ½ a teaspoon, a dash is ⅛ of a teaspoon. a pinch is 1⁄16 of a teaspoon, a smidgen is 1⁄32 of a teaspoon, and a drop is 1⁄64 of a teaspoon. Other amounts are available. A smidgen could be anything between 1⁄25 and 1⁄48, with 1⁄32 of a teaspoon being the most commonly used.

A tad is a small amount or a little bit, and used to mean a street boy or urchin in US slang. It probably comes from tadpole, which comes from Middle English taddepol, from tadde (toad) and pol(le) (scalp, pate).

A dash is a small quantity of a liquid and various other things. It comes from Middle English daschen/dassen (to hit with a weapon, to run, to break apart), from Old Danish daske (to slap, strike).

A smidgen is a very small quantity or amount. It is probably based on smeddum (fine powder, floor), from Old English sme(o)dma (fine flour, pollen meal, meal). Or it might be a diminutive of smitch (a tiny amount), or influenced by the Scots word smitch (stain, speck, small amount, trace). Alternative forms of smidgen include smidge, smidget, smidgeon and smidgin.

A pinch is a small amount of powder or granules, such that the amount could be held between fingertip and thumb tip, and has various other meanings. It comes from Middle English pinchen (to punch, nip, to be stingy), from Old Northern French *pinchier, possibly from Vulgar Latin *pinciāre (to puncture, pinch), from *punctiāre (to puncture, sting), from Latin punctiō (a puncture, prick) and *piccāre (to strike, sting).

A drop a very small quantity of liquid, or anything else. It comes from the Middle English drope (small quantity of liquid, small or least amount of something) from Old English dropa (a drop), from Proto-West Germanic *dropō (drop [of liquid]), from Proto-Germanic *drupô (drop [of liquid]),from Proto-Indo-European *dʰrewb- (to crumble, grind).

Do you know any other interesting words for small amounts or quantities?

Sources:

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://practical-parsimony.blogspot.com/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tad#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dash#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pinch#English

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/drop#English