Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language?

Things can be newfangled, but can they be oldfangled or just fangled?

Newfangled is used, often in derogatory, disapproving or humourous way, to refer to something that is new and often needlessly novel or gratuitously different. It may also refer to something that is recently devised or fashionable, especially when it’s not an improvement on existing things. It can also mean fond of novelty [source].

The word newfangle also exisits, although it’s obsolete. As a verb it means ‘to change by introducting novelties’, and as an adjective to means ‘eager for novelties’ or ‘desirous of changing’ [source]. It comes from the Middle English word neue-fangel, which meant fond of novelty, enamored of new love, inconstant, fickle, recent or fresh [source].

Things that are old-fashioned, antiquated, obsolete or unfashionable can be said to be oldfangled [source]. Things can also be fangled, that is, new-made, gaudy, showy or vainly decorated. Something that is fangled could be said to have fangleness [source].

The word fangle also exists, although it is no longer used, except possibly in some English dialects. It is a backformation from newfangled. As a verb it means to fashion, manufacture, invent, create, trim showily, entangle, hang about, waste time or to trifle. As a noun it means a prop, a new thing, something newly fashioned, a novelty, a new fancy, a foolish innovation, a gewgew, a trifling ornament, a conceit or a whim.

Fangle comes from the Middle English fangelen, from fangel (inclined to take), from the Old English *fangol/*fangel (inclinded to take), from fōn (to catch, caputure, seize, take (over), conquer) from the Proto-West Germanic *fą̄han (to take, seize), from the Proto-Germanic *fanhaną (to take, seize, capture, catch) [source].

Words from the same roots include fang (a long, pointed canine tooth used for biting and tearing flesh) in English, vangen (to catch) in Dutch, fangen (to catch, capture) in German, and få (to get, receive, be allowed to) in Swedish [source].

A Wanderwort is term used in linguistics to refer to a word that has spread to many different languages, often via trade. It was borrowed from German and comes from wandern (to wander) and Wort (word), so it’s a “wandering word”. The plural is Wanderwörter, Wanderworte or Wanderworts [source]. The origins of some such words goes back to ancient trade routes from the Bronze Age, and it can be difficult to trace which language they ultimately came from. Examples include copper, silver, mint and wine [source].

Another example of a Wanderwort is:

tea, which comes from the Dutch thee (tea), from 茶 (tê – tea) in the Amoy dialect of Southern Min (Min Nan), from the Old Chinese *l’aː (bitter plant), from the Proto-Sino-Tibetan *s-la (leaf, tea) [source].

There are similar words for tea in many other languages, including ᑎᕀ (tiy) in Cree, tae in Irish, tī in Maori and టీ (ṭī) in Telugu. These words arrived in Europe and elsewhere thanks to the Dutch East India Company, who brought tea by sea from Amoy [source].

The word chai which in English is short for masala chai, refers to a beverage made with black teas, steamed milk and sweet spices, based loosely on Indian recipes. It comes from from the Hindi-Urdu चाय / چائے (cāy – tea), from the Persian چای (čây – tea), from the Chinese 茶 (chá – tea) [source].

Languages that got their tea overland generally have a word for tea like chai or cha, including цай / ᠴᠠᠢ (tsay – tea) in Mongolian, चाय (cāy – tea) in Hindi, чай (čaj – tea) in Russian, ชา (chaa – tea) in Thai, and ca (tea) in Malay [source].

If you have slept well, you might say that you have slept like a baby, like a log, like a rock, like a top or like a lamb. Apparently in Chaucer’s time you might have said that you had slept like a swine, or whatever that was in Middle English [source].

If you search for “sleeping” on Flickr, as I just did, you mainly get photos of sleeping cats and sleeping babys, so maybe you could also say that you slept like a cat. The cat in the photo above is my sister’s cat Fletcher, by the way.

In Welsh you might sleep like a hog / wild boar (cysgu fel twrch), or like a hedge (fel clawdd), like a sow (fel hwch), like a pig (fel mochyn), like a small rope/cord (fel cordyn), like a nail (fel hoelen), like a stone (fel carreg) or like a mole (fel gwadd) [source].

In Scottish Gaelic you could say bha cadal nam maigheach orm (I slept like a hare), and cadal nam maigheach ort!, or literally “sleep of the hare on you”, is how you say “sweet dreams, sleep tight!” or something similar [source].

In French you might sleep like a dormouse (dormir comme un loir), like a marmot (comme une marmotte), like a stump (comme une soche), like a baby (comme un bébé) or with closed fists (à poings fermés) [source].

What about in other languages?

The word 謝る (ayamaru – to apologise) has been popping up in my Japanese lessons on Duolingo recently, and I thought it would be interesting to look into the ways the character 謝 is used in Chinese and Japanese.

In Mandarin Chinese the usual way to say thank you is 谢谢 [謝謝] (xièxiè). If you want to say many thanks or thanks a lot you might say 多谢 [多謝] (duōxiè) or 感谢 [感謝] (gănxiè), or even 太感谢了 (tài gănxiè le). Other ways to express your thanks are available.

The character 谢 (xiè), in combination with other characters, can mean various other things:

*the appearance of the performers at the conclusion of a theatrical or other performance in response to the applause of the audience [source].

The same character in Japanese means to apologise, and various other things. Here are some examples of how it’s used.

In Cantonese there are several ways to say thank you, including:

Sources; LINE Dict Chinese-English, jisho, CC-Canto

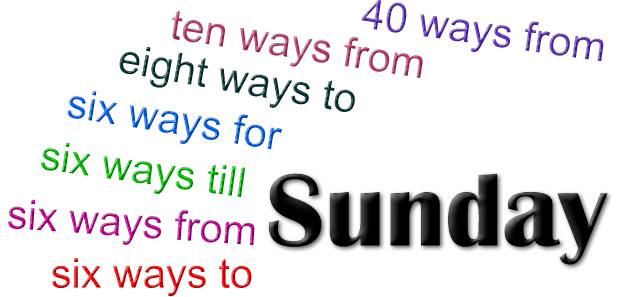

Six ways to Sunday is apparently an American expression that means ‘in every possible way, with every alternative examined’ or ‘in every possible direction’.

The first meaning can be found in “we checked him out six ways to Sunday before offering him that big loan.” while the second meaning is in “my necklace broke and the beads went six ways to Sunday”.

There are many variants on this phrase involving different numbers of ways ranging from two to a thousand. Some versions use different, both or many instead of numbers, and some replace to with from or for.

According to The Phrase Finder, the earliest known version of the phrase appeared in the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine in July 1832:

“[The horse] Nullifier, led to the post by a small dry looking man, with a hat that stands nine ways for Sunday, and whose antagonists quake at the sight of that old slouched beaver, as do the Bourbons still at the cocked hat of Napoleon.”

Another example from the same year, which appears in the novel Westward Ho! by James Kirke Paulding goes:

“Look!; they were stitched with a compass that pointed nine ways from Sunday”

The ‘six ways to Sunday’ version first appeared in The Chicago Tribune in November 1925.

World Wide Words quotes an earlier sighting of the phrase in Captain Francis Grose’s Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue from 1785:

“SQUINT-A-PIPES. A squinting man or woman; said to be born in the middle of the week, and looking both ways for Sunday; or born in a hackney coach, and looking out of both windows; fit for a cook, one eye in the pot, and the other up the chimney; looking nine ways at once.”

According to The Free Dictionary, this phrase means ‘Thoroughly or completely; in every possible way; from every conceivable angle.’ and variants include six ways to Sunday, six ways from Sunday, eight ways to Sunday, eight ways from Sunday, forty ways to Sunday and forty ways from Sunday.

Other variants of the phrase on Wiktionary include every way to Sunday, six ways till Sunday, six ways for Sunday, six ways before Sunday, ten ways from Sunday and nine ways to Sunday.

Have you heard this phrase before? Do you use it? Do you know any similar phrases in English or other languages?