How much is a smidgen? How about a tad, dash, drop or pinch?

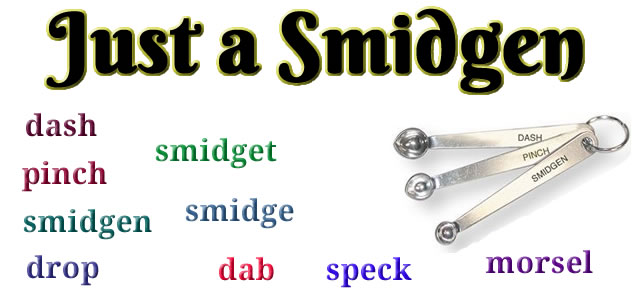

These are all terms that refer to small amounts of things. You might see them in a recipe, or use them to refer to other small quantities or amounts. You can even get measuring spoons for some of them.

Apparently a tad is ½ a teaspoon, a dash is ⅛ of a teaspoon. a pinch is 1⁄16 of a teaspoon, a smidgen is 1⁄32 of a teaspoon, and a drop is 1⁄64 of a teaspoon. Other amounts are available. A smidgen could be anything between 1⁄25 and 1⁄48, with 1⁄32 of a teaspoon being the most commonly used.

A tad is a small amount or a little bit, and used to mean a street boy or urchin in US slang. It probably comes from tadpole, which comes from Middle English taddepol, from tadde (toad) and pol(le) (scalp, pate).

A dash is a small quantity of a liquid and various other things. It comes from Middle English daschen/dassen (to hit with a weapon, to run, to break apart), from Old Danish daske (to slap, strike).

A smidgen is a very small quantity or amount. It is probably based on smeddum (fine powder, floor), from Old English sme(o)dma (fine flour, pollen meal, meal). Or it might be a diminutive of smitch (a tiny amount), or influenced by the Scots word smitch (stain, speck, small amount, trace). Alternative forms of smidgen include smidge, smidget, smidgeon and smidgin.

A pinch is a small amount of powder or granules, such that the amount could be held between fingertip and thumb tip, and has various other meanings. It comes from Middle English pinchen (to punch, nip, to be stingy), from Old Northern French *pinchier, possibly from Vulgar Latin *pinciāre (to puncture, pinch), from *punctiāre (to puncture, sting), from Latin punctiō (a puncture, prick) and *piccāre (to strike, sting).

A drop a very small quantity of liquid, or anything else. It comes from the Middle English drope (small quantity of liquid, small or least amount of something) from Old English dropa (a drop), from Proto-West Germanic *dropō (drop [of liquid]), from Proto-Germanic *drupô (drop [of liquid]),from Proto-Indo-European *dʰrewb- (to crumble, grind).

Do you know any other interesting words for small amounts or quantities?

Sources:

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://practical-parsimony.blogspot.com/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tad#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dash#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pinch#English

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smidgen#English

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/drop#English