This is a guest post by Dimitrios Polychronopoulos

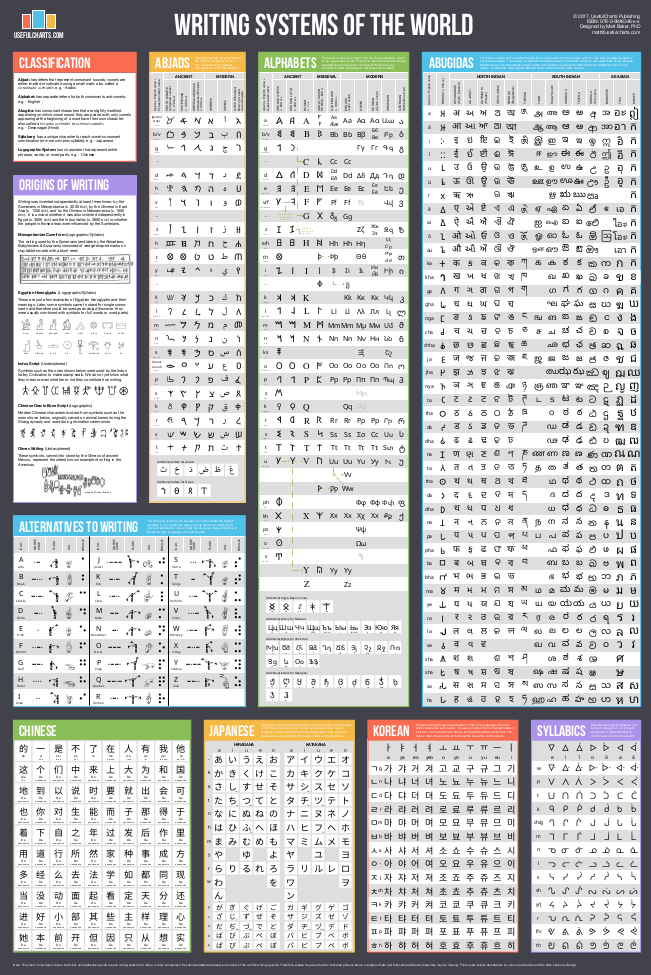

When I first started studying Chinese, in Taiwan, back in 1993, I started with the Mandarin phonetic alphabet and traditional characters. Primarily I used bopomofo to learn how to read, in the same way a Taiwanese child learns growing up on the island. Then just more than two years later, I left the island and found my progress in Chinese was mostly from books published the simplified characters. My tutors were from Beijing and Shanghai and I started learning the simplified characters.

Now more than twenty years have passed, and I’ve maintained my intermediate level of Chinese with a variety of tools. Back in 2015 I discovered LingQ and became a big fan and in 2016 I started my own website, Yozzi, to encourage myself to blog in different languages where I’d reached at least an upper intermediate level. The idea was for me to publish one article a week in each of my eight strongest languages. While I have been reasonably consistent at bringing new content to the site, so far I only have two articles up in Chinese. One of the greatest challenges is that when it comes to getting guest blogs on the site, I often have people saying they are interested in submitting, but they never get around to sending in their articles. The same thing happens with guest interviews. Several of the interviews have yet to be returned by the candidates who expressed their interest. One such interview is out there with a Chinese person who lives in Norway, but he hasn’t turned it in yet.

In this case could it be that Chinese is such an inconvenient language to write in? One of my Taiwanese friends who moved abroad says any time she has to write in Chinese, she always keeps putting it off, because even for her it is inconvenient. If a native Chinese speaker feels this way, no wonder as a non-native speaker, I myself have the fewest posts in Chinese up on Yozzi than any of the eight languages. I hope to change this in the long run. If there are any Chinese people who want to talk about their experiences in different countries, cross-culture experience and language-learning experience? I’d love to interview you for my site in Chinese. Please let me know

As for new ways to make progress in Chinese, in 2017 FlipWord has come along. I’ve been using FlipWord for nearly two months now. It’s been a lot of fun challenging my Chinese level. Anytime I want to read an article on line in English, I will open it up in my Chrome browser and let FlipWord replace English words with Chinese words. It will also quiz me as well from time to time on my syntax.

After United Airlines sent me an apology and an update about their changes after the terrible incident on board with the injuries of the passenger Dr. David Dao, I froze the letter in time with Chinese character changes, and published it on BeBee. With this letter, you can see an example of what FlipWord looks like if your settings are on ‘advanced’ for learning Chinese.

Regarding FlipWord, it feels good to see the new words and expressions I learn as I use it. It often happens that a word pops up in a context where I think I already know the word, but it presents me with a different option, for example to earn money I would normally think of “赚钱” Zhuànqián but FlipWord suggests 挣 ‘Zhēng’.

With FlipWord I find myself actively thinking about how I would express the same thing with my intermediate Chinese. There are many ways to express the same thing in a language. Language has nuances and shades. With FlipWord I’m beginning to understand nuances more than I expected to, with each new character that pops up. It also helps with syntax, as quizzes pop up and it asks me to construct my own sentences by putting characters in the right order. Another thing is that I never realised how bad my Chinese syntax was until FlipWord. At this point, my main question is how my learnings from FlipWord will become activated next time I find myself engaging in conversation among a group of native Chinese speakers. It’s the joy of the never ending tale and development of a lifelong language learner.