Feeling tired? Maybe it’s time for a snoozle.

Snoozle is a Scots word that means to snooze or doze, or to nuzzle, poke with the nose or snuggle [source].

Here are some examples of how it’s used:

- Just to keep you frae drowsying and snoozling

- Away! and snoozle yourself in your corner.

- A’m gonnae hae a richt guid snoozle the noo

I’m going to experience some high quality snuggling right now.

The last example comes from Miss PunnyPennie on TikTok, who inspired this post. You can hear how it at:

@misspunnypennie Did my loop work? 💙🏴 #scottish #scottishtiktok #scotland #scots #scotslanguage #merida #brave ♬ original sound – Miss PunnyPennie

It’s a blend of snooze and nuzzle and is found in some English dialects, where it means to nuzzle affectionately [source].

A snooze is a brief period of sleep or a nap, and as a verb it means to sleep, especially briefly; to nap or doze; or to pause or postpone for a short while. It’s origins are unknown [source].

Nuzzle means to touch someone or something with the nose, or to bring the nose to the ground, to burrow with the nose, or thrust the nose into [source]. It comes from the Middle English noselyng (face-downward, on the nose, in a prostrate position), from nose (nose, beak) and -lyng (a suffix denoting direction, state or position) [source].

There’s something about the combination of letters in snoozle that appeals to me, especially the sn and the oo.

Some other Scots words beginning with snoo include:

- snoofmadrune = a lazy or inactive person

- snooie = to toss the head as if displeased (of cattle)

- snoove = to become maudlin or sloppily sentimental

Are there words in other languages that have similar meanings?

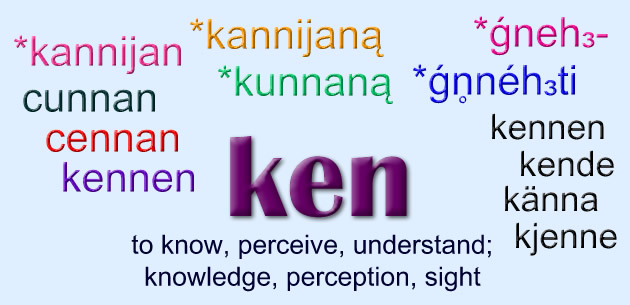

One I can think of is the Welsh/Wenglish word cwtsh/cwtch [kʊtʃ], which means a hug, cuddle, cubbyhole or little corner. It comes from the Middle English couche [ˈkuːtʃ(ə)] (bed), from the Old French couche (bed, lair), from couch(i)er (to lay down, place; go to bed, put to bed), from the Latin collocō (I place, put, settle) [source].