Some early alphabets, such as Ancient Greek, Latin and Etruscan were written in a style known as boustrophedon [ˌbuːstrəˈfiːdən], which involves alternate lines of a text being reversed, with letters also written in reverse. Here’s an example in Old / Archaic Latin:

The first and third lines of this text are written from right to left, while the second and fourth lines are written from left to right.

Transliteration

Opnēs hemones decnotāti et iouesi louberoi et parēs gnāscontor, rationes et comscientiās particapes sont, quibos enter sēd comcordiās studēōd agontinom est.

Translation

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

(Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

Translation (boustrophedon style)

The word boustrophedon could be translated literally as “like the ox turns [while plowing]”. It comes from βοῦς [bûːs] (ox), στροφή [stro.pʰɛ̌ː] (turn), and the adverbial suffix -δόν [dón] (like, in the manner of) [source].

From βοῦς we get such English words as beef, bovine, buffalo, butter and bulima [source], and the word cow comes from the same Proto-Indo-European root as βοῦς – *gʷṓws (cattle) [source].

The word στροφή is the root of the English word strophe, which refers to “A turn in verse, as from one metrical foot to another, or from one side of a chorus to the other”, and appears in words like apostrophe and catastrophe [source].

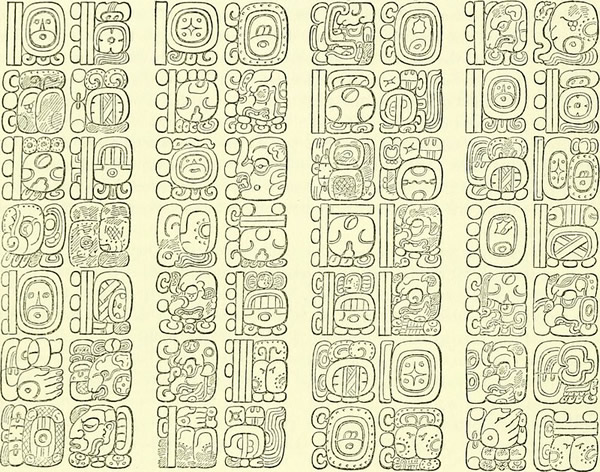

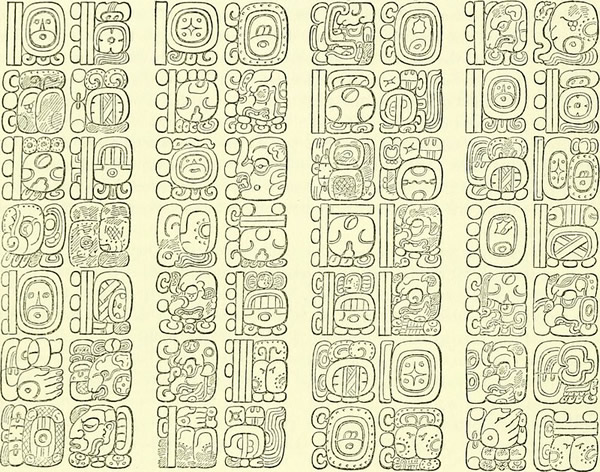

The old Mayan script was written in a way similar to boustrophedon: in paired columns zigzagging downwards from left to right.

From: Flickr

Chinese, Japanese and Korean could be also be written in this way but aren’t, as far as I know. They could also be written in other directions as illustrated below.

The text on the left starts on the top left and runs in vertical columns running from alternatively from top to bottom and bottom to top. The text on the right starts at the bottom right and runs in horizontal lines alternating from right to left and left to right.

If you’re thinking of created a writing system, one thing to consider is giving it a unique writing direction. This might inspire you.