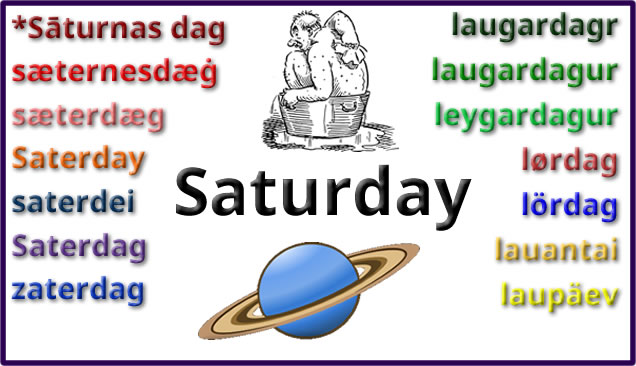

The English word Saturday comes ultimately from the Proto-West Germanic *Sāturnas dag (Saturn’s day), which is a calque (translation) of the Latin diēs Saturnī (day of Saturn).

There are similar words in other West Germanic languages, such as West Frisian (saterdei), Low German (Saterdag), and Dutch (zaterdag), all of which mean Saturday [source].

There German word for Saturday, Samstag, comes from Middle High German sam(e)ztac, from Old High German sambaztag (Sabbath day), from Gothic *𐍃𐌰𐌼𐌱𐌰𐍄𐍉 (*sambatō), a version 𐍃𐌰𐌱𐌱𐌰𐍄𐍉 (sabbatō – Saturday, the Sabbath day), from Koine Greek σάββατον (sábbaton – Sabbath), from Hebrew שַׁבָּת (šabbāṯ – Sabbath), possibly from Akkadian 𒊭𒉺𒀜𒌈 (šapattum – the middle day of the lunar month).

Words from the same roots include samedi (Saturday) in French, sâmbătă (Saturday) in Romanian, and szombat (Saturday, Sabbath) in Hungarian [source].

In northern and eastern Germany, another word for Saturday is Sonnabend (“Sunday eve”), as apparently in Germanic recking, the day begins at sunset. It a calque of the Old English sunnanǣfen (Saturday evening) [source].

Words for Saturday in the North Germanic languages have a different root, however. These include lördag in Swedish, lørdag in Danish and Norwegian, leygardagur in Faroese and laugardagur in Icelandic. They all come from the Old Norse laugardagr, from laug (pool) and dagr (day), so literally “bathing day” [source].

These words have also been borrowed into Finnic languages: Saturday is lauantai in Finnish, laupäev in Estonian and lavvantaki in Ingrian.

Are there any other languages in which Saturday means something like “bathing day”, or something else interesting?

See also: Days of the week in many languages on Omniglot.