What links the word satorial with the words tailor in various languages? Let’s find out.

The word sartorial means:

- Of or relating to the tailoring of clothing.

- Of or relating to the quality of dress.

- Of or relating to the sartorius muscle ( a long muscle in the leg.

It comes from New Latin sartorius (pertaining to a tailor), from Late Latin sartor (mender, patcher, tailor), from Latin sarcire (to patch, mend), sarciō (to patch, botch, mend, repair, restore, to make amends, recompense), from Proto-Indo-European *serḱ- (to mend, make good, recompense) [source].

Words from the same roots include sastre (tailor) in Spanish, Tagalog and Chavacano, xastre (tailor) in Asturian, Galician and Portuguese, sarto (tailor) in Italian, sertir (to crimp, set, socket [jewellery]) and the surname Sartre in French, and the obsolete English word sartor (tailor) [source].

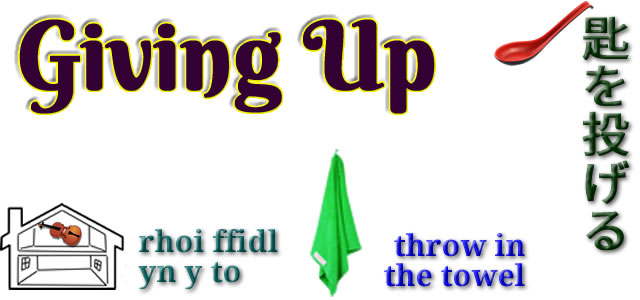

The English word tailor, which refers to a person who makes, repairs, or alters clothes professionally, especially suits and men’s clothing, comes from Middle English taillour (tailor), from Anglo-Norman tailloru (tailor), from Old French tailleor (tailor), from taillier (to cut, shape), from Late Latin tāliō (retaliation, to cut, prune), from Latin tālea (rod, stick, stake, a cutting, twig, sprig), the origins of which are uncertain [source].

Related words include tally (any account or score kept by notches or marks) in English, taille (size, waist) and tailler (to cut) in French, Teller (plate, dish) in German, táille (fee, charge) in Irish, talea (cutting, scion) in Italian, and taior (woman’s suit) in Romanian tajar (to cut, slice, chop) in Spanish [source].

I was inspired to write this post after learning that tailor in Spanish is sastre, and wondering where it comes from.

By the way, Happy New Year! Blwyddyn newydd dda! Bonne année ! ¡Feliz Año Nuevo! 新年快樂! 新年快乐! Felice anno nuovo! 新年おめでとうございます! Bliain úr faoi shéan is faoi mhaise duit! Bliadhna mhath ùr! Blein Vie Noa! Ein gutes neues Jahr! Feliĉan novan jaron! Поздравляю с Новым Годом! Šťastný nový rok! Godt nytår! Gott nytt år! La Mulți Ani! Onnellista uutta vuotta! 🎆🎉🥂🥳