Part of the process of learning a new language involves learning about the people who speak it, and about their culture(s), history and so on. You might also find yourself involved in the politics of when and how the language is used, especially if you’re learning a minority / endangered / revived language, or a non-standard version of a major language. This is certainly the case for the Celtic languages I’ve studied.

You might be told that there’s no point in learning a Celtic language as everybody who speaks them also speaks English, or in the case of Breton, French. This is not in fact true – there are people in Patagonia in Argentina who speak Welsh and Spanish, but not English, and there are some people who have learnt a Celtic language who don’t speak English or French.

People may object to children being ‘forced’ to learn such ‘useless’ languages in school, or they may complain that they had to learn them in school. Well, education usually involves learning things that you might have little or no interest in, but you never know, maybe it will be useful to know them one day.

Critics of minority languages might come from the country or region where they are spoken, but not feel part of the local culture as they don’t speak the local language. In Wales, for example, non-Welsh-speaking people are sometimes told by Welsh speakers that they are less Welsh or basically English. Fortunately this is not a common view among Welsh speakers. Also, people who don’t speak such languages could learn them, and will find that most native speakers will be support their efforts.

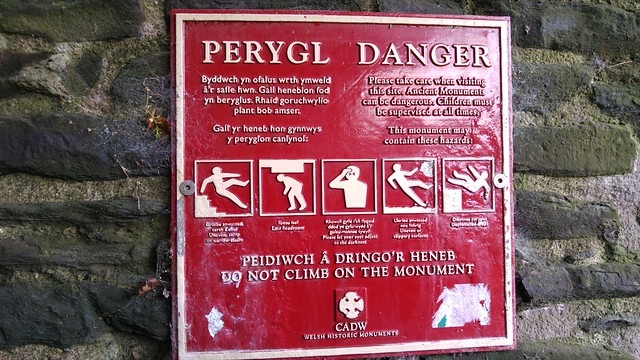

Also, why are they spending our taxes to support those useless languages? That’s a comment that often crops up whenever there’s discussion of bilingual or minority language education, bilingual signage and other material, and any other initiatives to support minority languages. Speakers of minority languages also pay taxes, you know.

Have you encountered any such linguistic politics?

Here’s an example of an article that discusses some of these issues.