Foods, and the words that describe them, can travel around the world. For example, tea comes from China, and so do words for tea in many languages. Similarly, avocado, chocolate, tamale, tomato come from Mexico (both the words and the foods).

Those words came to Europe from other continents, and I recently discovered some words that travelled from Europe, or Western Asia, to many other parts of the world.

It started with the Proto-Indo-European word *médʰu (honey, mead), which spread throughout Europe and Asia, and possibly as far as China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam [source].

Descendants of *médʰu include:

- մեղու [meʁú] = bee in Armenian

- мед (med) = honey in Bulgarian

- mõdu [mjøːd] = mead in Estonian

- Met [meːt] = mead in German

- μέθη (méthi) = drunkenness in Greek

- מותק (mótek) = sweetness in Hebrew

- मॊदुर / مۆدُر (modur) = sweet, tasty, delicious in Kashmiri

- medus [mædus] = honey, mead in Latvian

- މީރު [miː.ɾu] = pleasant, sweet, agreeable, savoury in Maldivian

- medveď [ˈmɛdvɛc] = bear (“honey-eater”) in Slovak

- mjöd [mjøːd] = mead in Swedish

- மதுரம் [mɐd̪ʊɾɐm] = sweetness in Tamil

- medd [meːð] = mead, and meddw [ˈmɛðu] = drunk in Welsh

The Irish name Méabh (Maeve) also comes from the same roots, via Middle Irish medb (intoxicating) [source]. For more details of related words in Celtic languages, see this Celtiadur post: Honey Wine

It also reached China, where it became mīt (honey) in Tocharian B, and was possibly borrowed into Old Chinese as *mit (honey), which became 蜜 (mì – honey) in Mandarin, 蜜 (mat6 [mɐt˨] – bee, honeybee) in Cantonese, 蜜 (mitsu – honey, nectar, moasses, syrup) in Japanese, 밀 (mil – beeswax) in Korean, and mật (honey, molasses) and mứt (jam) in Vietnamese [source].

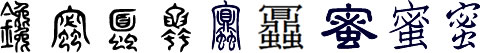

Evolution of the Chinese character for honey (蜜)

See also: https://hanziyuan.net/#蜜