Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

The Japanese word 賑やか / にぎやか (nigiyaka) means bustling, busy, crowded, lively, prosperous or thriving, and also loud, noisy, merry or cheerful. I find it very satisfying to say, which is why I chose to write about it today.

Here are some examples of how it’s used and related words (from Jisho.org and Reverso):

In Mandarin the character 赈 [賑] (zhèn) means to relieve or relief. It appears in such words as:

One Chinese equivalent of 賑やか is 热闹 [熱鬧] (rènao), which means bustling with noise and excitement, lively, to liven up, a spectacle, or literally “hot noisy”. Most Chinese people I know prefer places that are 热闹 to ones that are too 安静 (ānjìng – quiet, peaceful), and as most places in China and Taiwan are 热闹, this is probably a good thing.

Sources: LINE Dictionary Chinese – English, MDBG Word Dictionary

I generally prefer quiet, peaceful places, but occasionally don’t mind a bit of lively bustle. How about you?

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

An interesting Dutch word I learnt recently is kwetsen [ˈkʋɛtsə(n)], which means to hurt (sb’s feelings) or to harm, and in some Dutch dialects it means to wound or injure.

Related words include:

It comes from the Middle Dutch word quetsen, from the Old Dutch quezzon (to damage, hurt), and was possibly influenced by or borrowed from the Old French quasser (to break, annul, quash), from the Latin quassāre (to shake, agitate), from the Proto-Indo-European *kʷeh₁t- (to shake) [source].

The German word quetschen [ˈkvɛtʃən] (to squash, crush, squeeze, mash, strain) probably comes from the same root [source], as does the Yiddish word קוועטשן (kvetshn – to squeeze, pinch; bother, complain), from which we get the English word kvetch [kvɛtʃ] (to whine or complain, often needlessly and incessantly) [source].

Incidentally, the German equivalent of a squeezebox (an informal name for accordions, concertinas and related instruments) is a Quetschkommode, or literally a “squeeze commode / dresser / chest of drawers” [source].

The English word quash (to defeat decisively; to void or suppress) comes from the same Old French word (quasser), via the Middle English quaschen, quasshen, cwessen, quassen (to crush, smash, cancel, make void, shake) [source].

From the same PIE root (*kʷeh₁t-) we get the English words pasta, paste, pastiche and pastry [source]. Pasta, for example, comes from the Italian pasta (paste, pasta), from the Late Latin pasta (dough, pastry cake, paste), from the Ancient Greek πάστα (pásta – barley porridge), from παστός (pastós – sprinkled with salt), from πάσσω (pássō – to sprinkle) [source].

If your hands and fingers become quobbled, should you be worried?

Quobbled is an dialect word from Wiltshire in the south west of England that means wrinkly – so there would be no need to worry, it’s just a temporary phenomenon.

According to Words and Phrases from the Past, quobbled is defined as:

quobbled, adj. of a woman’s hands: shrivelled and wrinked from being too long in the washtub (English dialect)

Another definition is found in A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Wiltshire

By George Edward Dartnell, and Edward Hungerford Goddard (1893):

quobble. n. and v. After being a long while in the washtub a woman’s hands are apt to get ‘all in a quobble,’ or ‘ter’ble quobbled,’ that is, shrivelled and drawn and wrinkled up.

In Joseph Wright’s 1903 book, The English dialect dictionary, being the complete vocabulary of all dialect words still in use, or known to have been in use during the last two hundred years; founded on the publications of the English Dialect Society and on a large amount of material never before printed. (they really went in for short, snappy title back then), we find:

quobble, v. Of water: to make a noise in boiling

Then there’s:

quob, sb. and v.

1. A marshy spot; a bog, quagmire; a quicksand.

2. all of a quob, in a mess; in a heap; a bad bruise

3. an unfirm layer of fat

4. A throb; a palpitation

5. v. To quiver like jelly; to throb, to palpitate

Related words include:

Apparently quob comes from the East Friesian kwabbeln / kwobbeln (to tremble, vibrate). This is probably related to the West Frisian word kwab (weak, blubbery mass of fat or flesh; very fat person; brain lobe; jellyfish) [Source], and the Dutch word kwabbig (flabby, squishy) [Source]

Some other interesting words from Wiltshire dialect include:

Source: A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Wiltshire.

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

What would you buy in a ferretería?

When I first saw this (Spanish) word, I thought it was a shop that sells ferrets. I was slightly disappointed to discover that it actually means hardware, or hardware store or ironmongers. Or in other words, a place selling things made of ferrous metal (iron).

It comes from ferrete (branding iron), from the Old French ferret (branding iron), a diminutive of fer (iron), from the Latin ferrum (iron); and -ería (a suffix that turns a noun into a store or restaurant that sells such an item; characteristic of) [source].

A shop selling ferrets (hurones) would be a huronería, and the Spanish word for ferret, hurón, comes from the Latin fūr (thief), which is also the root of the English word ferret [source]. More about ferrets.

Other words for hardware store in Spanish include:

Other words ending in -ería include [source]:

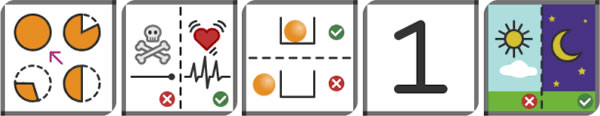

Recently I was sent details of a image-based communication system that is being developed by some friends of mine at KomunIKON. It’s known as IKON, and according to their website:

IKON is an easy, intuitive, international and transcultural visual language. It is a structured system of graphical communication that combines icons and linguistics.

By being fun and creative, IKON has applications in different fields, from communication technology to graphic design, education, product merchandise and humanitarian crisis support.

Here are some examples – see if you can work out what they mean:

All the examples on the KomunIKON website, and the ones they sent to me, include English labels under each image. The word order for each one is based on English, but apparently “the IKON language is very flexible, so the grammatical explanations that we offer here are meant to show some ideas behind our icons, but they are not rigid rules to be learnt, anyone can use the language as they prefer, as far as the receiver understands.”

So we have a visual communication system without grammatical conventions. That doesn’t sound like a language to me. What do you think?

Here’s a recording in a mystery language.

Do you know or can you guess the language, and do you know where it’s spoken?

I am currently (re)learning Japanese, and am noticing some differences between the meanings of characters in Japanese (漢字 – kanji) and in Chinese (汉字 [漢字] hànzì). In some cases the meanings are similar but subtly different, in other cases they’re completely different.

For example, in Mandarin Chinese 高 (gāo) means tall or high (高的 gāode), or senior (高级的 gāojíde), while in Japanese 高 (taka), means quantity, amount (of money), volume or number, 高い (takai) means high, tall, expensive, above average or loud, and 高 (kō) means high (school).

The Chinese word for expensive is 贵 [貴] (guì), which also means valuble. In Japanese this character, 貴 (ki), means your, and indicates high rank, status, love or respect. Or when it’s pronounced mochi it means lord, god, goddess, and is used in honorific title for deities and high-ranking people. One Japanese word for you is あなた (anata), which is usually written in hiragana, but can be written with the kanji 貴方. In very formal written Chinese 贵方 [貴方] (guìfāng) can be used to mean you.

The Japanese word for cheap is 安い (yasui), while the same character in Chinese, 安 (ān), means quiet or safe. The Chinese word for cheap is 便宜 (piányi), which in Japanese is pronounced bengi and means convenience, accommodation, advantage, benefit or expediency.

The character 便 is also pronouned biàn in Mandarin, and means convenient, convenience and to excrete. It appears in the word 便利 (biànlì) = convenient, to faciliate, which also exists in Japanese as 便利 (benri) meaning convenient, handy or useful.

The character 利 (lì) means sharp, advantageous, interest or to profit in Mandarin. In Japanese it’s pronounced ri and means advantage, benefit, profit or interest. It appears in the word 利益 (lìyì / rieki), which means benefit in Mandarin, and profit or gains in Japanese, and also in 利害 (lìhai / rigai) which means terrible in Mandarin, and advantages and disadvantages in Japanese. Which should not be confused with 厉害 [厲害] (lìhai), which means terrbile, terribly or awesome, and is used as a general intensifier in Mandarin. The equivalent in Japanese is 素晴らしい (subarashī).

There are many more. Have you noticed any?

Sources: LINE Dict Chinese-English, jisho.org