Podcast: Play in new window | Download

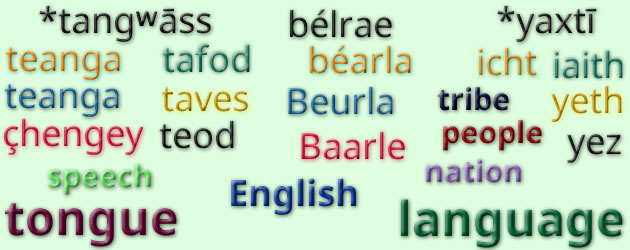

In this episode we’re looking at words for person, human and related things.

In Proto-Celtic a word for person was *gdonyos, which comes from the Proto-Indo-European *dʰéǵʰom-yo- (earthling, human), from *dʰéǵʰōm (earth, human) [source].

Descendents in the modern Celtic languages include:

- duine [ˈd̪ˠɪnʲə] = human, man, mankind, person in Irish

- duine [dɯn̪ʲə] = fellow, person, man, husband in Scottish Gaelic

- dooinney [ˈd̪uːnʲə] = human, man, fellow, husband in Manx

- dyn [dɨːn / diːn] = man, human being; person, and dynes [ˈdənɛs] = woman in Welsh

- den [dɛ:n / de:n] = man, guy, human, person in Cornish

- den [ˈdẽːn] = human being, person, man, husband in Breton

Another Proto-Celitc word from the same PIE root is *gdū (place), which became dú (place, inheritance; native, natural, proper, fitting) in Modern Irish, dùth (natural, hereditary, proper, fit, suitable) in Scottish Gaelic, and dooie (complement, inherent, natural, patriotic) in Manx [source].

Other words from the same PIE root include: human, humus, bridegroom in English; goom, an old word for man in northern English dialects and Scots; gumi, a poetic word for a man in Icelandic, and hombre (man, husband) in Spanish [source].

Incidentally, the English word dean is not related to these words – it comes from the Middle English de(e)n (dean), from the Anglo-Norman deen and from the Old French deien, from Latin decānus (chief of ten people, dean), from decem (ten) and -ānus (of or pertaining to) [source].

Words for man and people in some Native American languages sound similar to, though are not related to these Celtic words. For example, diné (person, man, people) in Navajo comes from di- (thematic prefix relating to action performed with the arms and legs) and -né (man, person) [source].

There are also words for people in Celtic languages that were borrowed from the Latin populus (people, nation, community):

- pobal [ˈpˠɔbˠəlˠ] = people, community, parish, population in Irish

- poball [pobəl̪ˠ] = folk, people, community in Scottish Gaelic

- pobble = people, population, community in Manx

- pobl [ˈpʰɔbl̩ˠ / ˈpɔbɔl] = people, public, nation, tribe in Welsh

- pobel = people in Cornish

- pobl = people, multitude in Breton

More details about these words on Celtiadur, a blog where I explore connections between Celtic languages in more depth.

I also write about words, etymology and other language-related topics on the Omniglot Blog.

You can also listen to this podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Stitcher, TuneIn, Podchaser, PlayerFM or podtail.

If you would like to support this podcast, you can make a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or contribute to Omniglot in other ways.