Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Here’s the latest news from the world of Omniglot.

There are new language pages about:

- Äiwoo, an Oceanic language spoken mainly in the Reef Islands in Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands.

- Iaai, a Southern Oceanic language spoken in New Caledonia.

- Dumi (दुमी), a Kiranti language spoken in eastern Nepal.

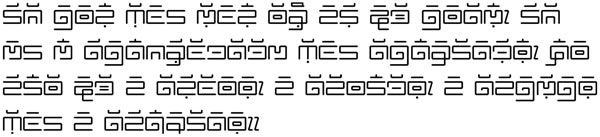

There’s a new constructed script called Altus, which was devised by Paul Mbongo as an alternative way to write Lingala, a Bantu language spoken mainly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in the Republic of Congo.

There are new numbers pages in:

- Wapishana (Wapixana), a Northern Arawakan language spoken in Guyana and Brazil.

- Yaghnobi (yaɣnobī́ zivók / яғнобӣ зивок), an Eastern Iranian language spoken in the Yaghnob valley in northwestern Tajikistan.

- Dumi (दुमी), a Kiranti language spoken in eastern Nepal.

There’s a new page with family words in Urdu.

There’s a new Tower of Babel translation in Iaai.

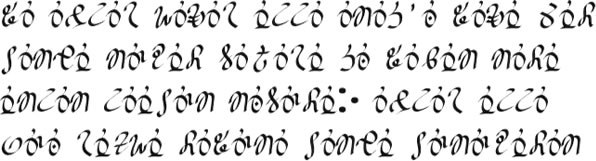

On the Omniglot blog this week there’s a post called Different Worlds, which is about the Japanese stories known as isekai (different world), and the linguistic situations in such worlds, and the usual Language Quiz. See if you can guess what language this is:

Here’s a clue: this language is spoken in the USA.

The mystery language in last week’s language quiz was

Nheengatu (ñe’engatú), a Tupí-Guarani language spoken in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela.

There’s a new Celtiadur post about words for flour and related things in Celtic languages.

On the Celtic Pathways podcast we are digging up the origins of the word Iron.

In this week’s Adventure in Etymology we’re looking into, examining, scrutinizing and underseeking the origins of the word investigate.

In other news. this week my current streak on Duolingo passed 1,900 days, and yesterday I got to 1,904 days. So with my previous 96-day streak, I have now been studying languages every day for the past 2,000 days, or about five and a half years. In that time I’ve completed courses in Swedish, Russian, Danish, Romanian, Czech, Esperanto and Dutch. I also finished all the Spanish lessons, but then they added a whole bunch of new ones, which I’m working on those at the moment. I’m also refreshing my Japanese and Scottish Gaelic.

Do I speak all these languages now? Well, yes and no. I speak some of them fairly well, and can at least have basic conversations in the others. Some I understand and can read better than I speak or write them. The one I know the least of is Romanian, which I hadn’t studied before and tried to learn just using Duolingo. I found it difficult trying to work out the grammar, and there were no explanations.

Recently I’ve been enjoying using Super Duolingo (formerly Duolingo Plus). Normally you have to pay a monthly subscription for it, but I can use it for free, thanks to people who have signed up via one of the links on Omniglot. For each person that signs up, I get a free week. Would it be worth paying for this? Maybe, if you can afford it. You don’t have to worry about making mistakes as you don’t run out of hearts, except in the crown levels, you can practise your mistakes and take tests.

Have you tried Super Duolingo? If so, what do you think of it?

For more Omniglot News see:

https://www.omniglot.com/news/

https://twitter.com/Omniglossia

https://www.facebook.com/groups/omniglot/

https://www.facebook.com/Omniglot-100430558332117

You can also listen to this podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Stitcher, TuneIn, Podchaser, PlayerFM or podtail.

If you would like to support this podcast, you can make a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or contribute to Omniglot in other ways.